True story of two teenagers and the crime that changed their lives

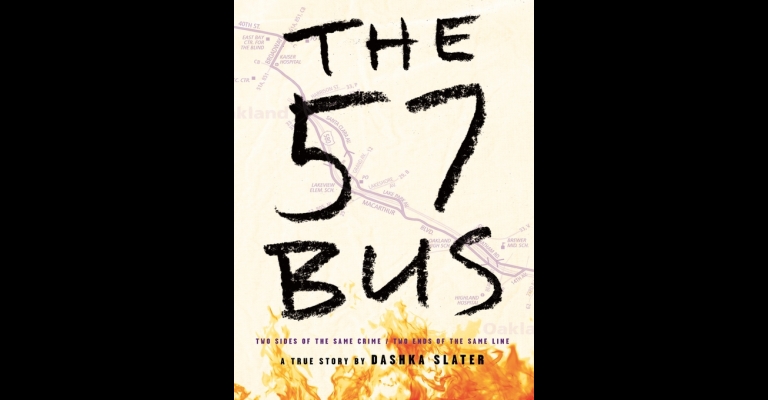

“The 57 Bus” by Dashka Slater

Farrar Straus Giroux, 2017

It’s November 4, 2013 in Oakland, California. The 57 bus is lumbering along its 11-mile route from the well-to-do houses in the hills to the impoverished neighborhoods in the flatlands where two-thirds of the city’s murders occur.

Amid passengers commuting home from work and students returning from high school, there are two teenagers who share the route for only eight minutes. One of them is Sasha, an agender white student with Asperger’s, who goes to a small private high school. The other is Richard, a 16-year-old black student who is struggling toward a diploma at Oakland High.

Richard is joined by two friends, and they’re fooling around in the back when one of them notices that Sasha, who is napping, is wearing a gauzy skirt. Handing his cigarette lighter to Richard, he urges him to set Sasha’s skirt alight. A minute or two later, Sasha awakens in a ball of fire; during the next weeks, Sasha’s third-degree burns require multiple operations. The surveillance video on the 57 bus leads the police to arrest Richard at school the next day; accused of a hate crime and charged as an adult, he faces life in prison. According to the media and many of the people who are shocked by the crime, the sentence is exactly what Richard deserves.

“The 57 Bus” describes a tragic situation that is far more complicated than it seems. Piecing together interviews, documents, videos, diaries, and social media posts, Slater, who originally covered the story for The New York Times, begins the book with careful portrayals of Sasha and Richard. In short chapters, she follows Sasha’s progress from boyhood as Luke to acceptance of a non-binary gender, and their support from their friends and parents.

Along the way, Slater explains the terminology that Sasha and their friends use – including calling a non-binary person “they,” instead of “he” or “she” – thus introducing many readers to an unfamiliar state of mind. The next succession of short chapters portray Richard. His mother, who was 15 when he was born, is hardworking and loving, but the atmosphere in which he matures is grim: cousins and aunts are killed by gunfire and a “friend” robs him at gunpoint. He’s known to be a bit of a goofball; he skips school, has been sent to a disciplinary juvenile home for joining a fight – but his friends and teachers agree he’s “a good kid” who is struggling to become responsible. So why…? So how …?

As Slater describes the fire and the events after it, a third portrait emerges: a criminal justice system gone wrong. Interviewed by the police without a parent or lawyer present, Richard misuses the term ‘homophobic.” The word immediately defines his act as a hate crime and leads to the possibility of his being tried as an adult, not a juvenile. And yet, there is little hate in this book.

Horrified by the unintended results of his action (he expected at most a burn hole), Richard writes two letters of deep apology to Sasha. Both, however, are waylaid by his lawyer, who realizes that they will be used as admissions of guilt; Sasha and their parents get them only 14 months after the fire. Richard takes full responsibility for the crime; nobody seems to notice that he has never snitched on the friends who gave him the lighter – and who were never interviewed or charged. The case drags on. Sasha, fully recovered, goes to MIT; Richard still is in danger of life imprisonment. But working against the power of the law is the power of forgiveness, as Sasha and their parents plead that Richard be charged as a juvenile.

This is a truly impressive book. Never biased, never sentimental, consistently heart-breaking, it challenges everyday assumptions that affect even the most liberal readers. You can’t afford not to read it.

Laura Stevenson lives in Wilmington and her most recent novels, “Return in Kind” and “Liar from Vermont,” are both set on Boyd Hill Road.